When I think about all the places I’ve visited in the world, I remember my one constant travel companion.

I’ve only owned two cameras – if you don’t count my numerous i-phones - and have no idea whether that is normal, too few or extravagant. My first was a Canon EOS 500 back in the days when film was all that existed and there was an agonising wait for the developers to send back the prints, waiting to see if they were out of focus, knowing there was no such thing as a second chance. The cost of a camera in the 1980’s seemed like a small fortune, but I was in my 20’s and not earning much even by the standards of the day. So when I got an unexpected bonus, I invested in two lenses and a tripod. It all seemed very advanced for its time and although I learnt most of the camera’s functions through books, what I really discovered by trial and error was a way to connect my mind, body and spirit to seeing something magical through the lens. It was like discovering a secret layer.

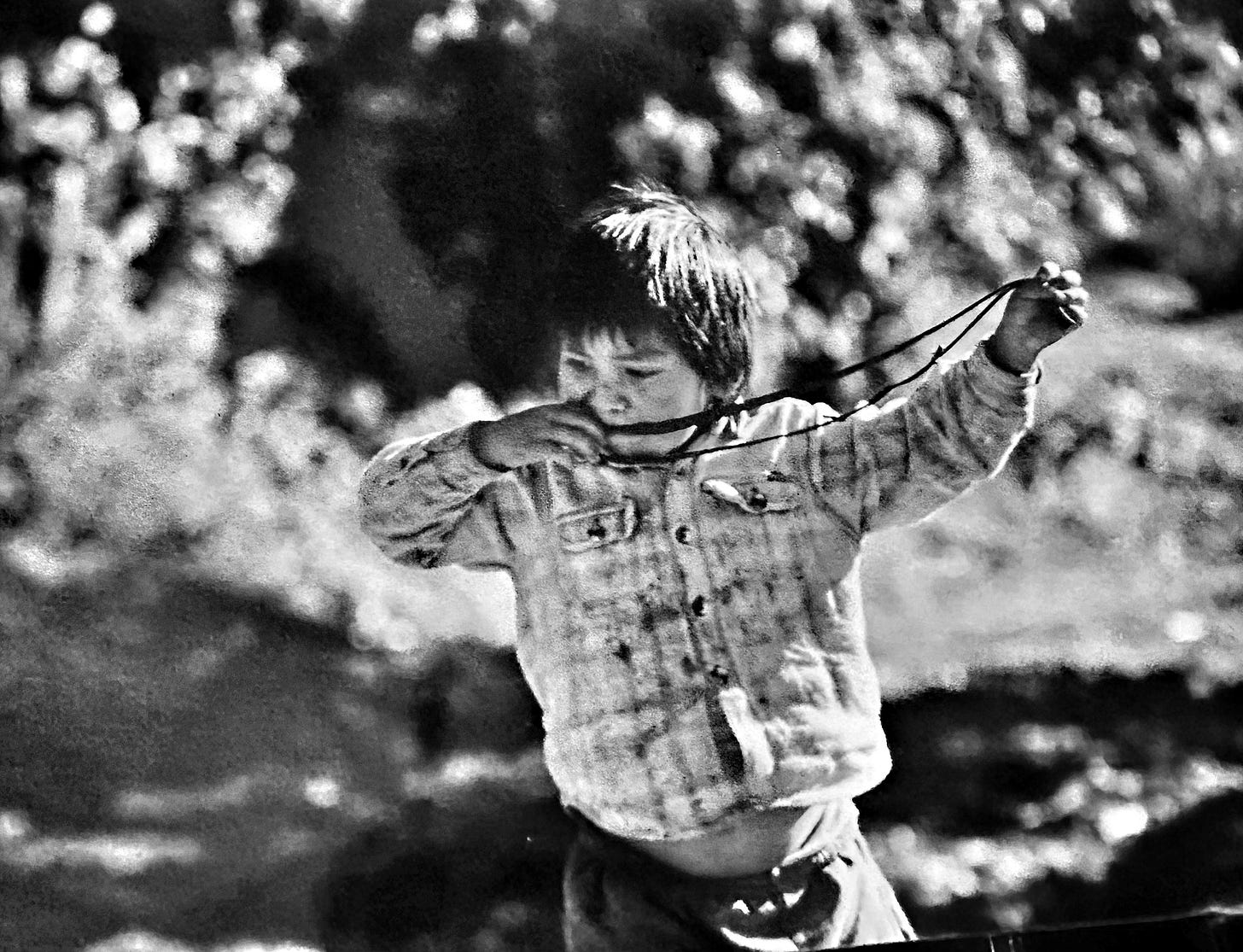

I was at my happiest, and together we travelled the world, sitting in cafes, watching places and people, even making some spare cash from selling images to travel magazines. It was all about capturing a career and a life with all its highs and flaws. The stunning, rich scenes alongside the reality of people’s lives that never seemed more than a street corner away. Captured in one moment, people silently gathered in the cathedral square whilst around the corner, the heavily armed military waited for the signal to move. When the Soviet Union collapsed, I stood in Red Square and captured the faces of people who seemed weary, hesitant yet eager for a new era, little knowing what lay ahead. For the month I stayed in the Sacred Valley of the Incas just outside Cusco in Peru, my camera captured the simple, unhurried life that was a million miles from my own in London. Every morning, I walked along a small river followed by a young boy, no more than six years old, with a muddy face and red cheeks from a life lived outdoors in high altitudes clutching onto a bit of elastic, yet always bathed in the morning sunlight, full of mischief and never standing still. He spoke the local dialect, and I spoke Spanish… badly. When I asked his name, he replied “Urco”. I later found out that his name was Kevin, so rather less in keeping with the spiritual surroundings of the pathway to Machu Picchu, but a sign of how far US daytime TV travels. What I thought was a name was the local word for catapult, the bit of elastic he faithfully carried.

The camera and I continued our travels until my career’s unplanned progression slipped into leadership. The title and salary followed. But I lost so much of my spirit, consumed by the endless meetings, spreadsheets and funding bids. I put my camera down and waited 25 years to pick it up again. The world moved on and digital soon replaced the way we captured images. Thousands, millions even were readily available, and the concept of the stock image grew a huge industry. Now, anyone who knows me will appreciate that if there is one thing I loathe more than anything else, it’s a stock image when the subject is a human being. It just doesn’t work for me. A few years ago, I conceived a national science campaign to get society behind all the valuable and exciting futures that were available for young people from all sorts of backgrounds to save their planet and its inhabitants - human and non human. It was to be a provocative piece of work that wasn’t afraid of breaking the rule book to push people out of their comfortable, stereotyping zone. So, imagine how I winced when the campaign started to feature stock images that yelled – stock image. I can understand why time constraints and money drove the decision but does anyone still remember the image used by a major UK charity for a campaign to address poverty – a small white child, dirty clothes, standing in a puddle, looking forlorn against the dark, moody backdrop of a run-down estate. It didn’t work probably because it’s difficult to tackle people’s pre-conceived ideas with stereotype. Sure, poverty exists but in many guises. Some are subtle and nuanced and not easily captured in a single frame. There is never a single narrative to anyone’s story where most people live their lives in contrasting colours, grey and texture. In the era of digital manipulation and fast fire opinion over fact, we have to think about this every time we communicate about social and political issues.

There was one time in my career when I think that I got it right and that was largely thanks to a very well-known physicist called Professor Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell – I’m sure I’ve mentioned her before – and a very talented storyteller and photographer who has done a lot of work on community projects. Dame Jocelyn had donated a considerable amount of prize money from her Breakthrough Award to help young people from many different backgrounds to continue with their PhDs. The brief I gave to the storyteller was to film and capture still images of a group of young students from very different walks of life who were part of a new scholarship programme thanks to Dame Jocelyn’s generosity. The brief was beautifully executed and the result was a powerful artistic expression of the person behind the life of a scientist. The photos needed no captions. Every image gave a multi-layered story. They didn’t only reflect the studying but meeting up with friends, getting on with normal, everyday life as well as being a research scientist. Each image gave a life story to a human being whom others could relate to - and wanted to be. I guess the modern day word is authentic.

It wasn’t until I had a big change in my life that I picked up a camera again. This time, investing in a Sony A7 iii. It’s a good, solid, digital beast. Slowly I’m getting used to the new world of digital photography but most importantly I’m starting to find my focus. For reasons I don’t understand I’m drawn to nature more than people and street photography, fascinated by the role nature has in science and finding the sources of innovative treatments that are part of modern health. I’m told this is entirely normal (nature, not the science obsession!) and hardly surprising that my career now includes my work as CEO of a wonderful environmental charity. Yet I can feel an almost physical tug away from photographing people which doesn’t seem normal at all. What’s stopping me? I really hope that changes because it’s still where my heart is, and I know there is more to come.

I didn’t get to finish something important and I refuse to leave it undone. I really hope the creative best is yet to come…..